"POURING Coca-Cola in the cabernet, Sofia Coppola's dazzling "Marie Antoinette" couldn't be more anachronistic if it showed the queen of France saying, "Let them eat sushi." Coppola works in weird ways, but the real Versailles was so much weirder.

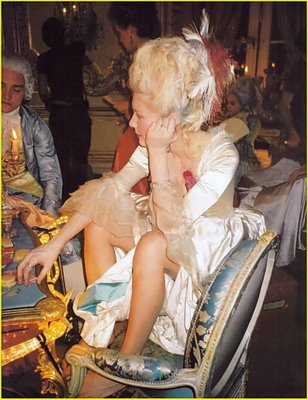

Just as Tobey Maguire proved that the superhero is about the vulnerability, Kirsten Dunst nicely unveils the innocence in the doomed queen of France.

The 1980s score and 818 dialogue ("I love your hair! What's going on there?") may strike you as a little too droll for l'école. But the story follows Antonia Fraser's biography, and the crazy flourishes simultaneously blast away the musty mists of history and make the audience feel, as the Austrian-born queen must have, lost in translation. [...]

Dunst, tearfully parting with her pug as her character exits Austria, practically has a dotted line around her neck with instructions to "cut here," and she makes no effort to starch up her squeaky American cuteness. But though the real Marie Antoinette was born an archduchess, she was no older than a highschool freshman when she married. After that, she was just a victim of fashion, a pleated skirt when history went Goth. Her story could just as easily be called "Clueless."

kyle.smith@nypost.com Source: The New York Post

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Sofia Coppola is the Veruca Salt of American filmmakers. She's the privileged little girl in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory whose father, a nut tycoon, makes sure his daughter wins a golden ticket to the Willie Wonka factory by buying up countless Wonka bars, which his workers methodically unwrap till they find the prize. If Coppola's 2004 Academy Award for best original screenplay for Lost in Translation was her golden ticket to big-budget filmmaking, Marie Antoinette is her prize, a $40 million tour through the lush and hallucinatory candy land of 18th-century France. Of course, Roald Dahl's insufferable Veruca Salt was eventually seized by angry squirrels and hurled down a garbage chute. [...]

Given the film's cavalier treatment of their country's history, French critics, understandably, head up the haters' brigade. Agnès Poirier, the London correspondent for Libération, scoffs, "There are two things [Coppola] likes, dresses and pudding. ... Cinema is for Coppola a mirror in which she looks at herself, not a mirror she holds to the world." But many critics on both sides of the Atlantic defend the film, in indulgent language that often seems to apply to its creator as well. To Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwarzbaum, Marie Antoinette is "the work of a mature filmmaker who has identified and developed a new cinematic vocabulary to describe a new breed of post-postpostfeminist woman." (The triple negative threw me for a minute, but I think she means "not feminist.")

There's no question that making movies is, at least in part, always a matter of shopping. A director must select, and find a way to pay for, the right cast, the right music, the right cinematographer. And, as this recent piece in the Times travel section shows, Sofia Coppola is a peerless shopper. The movie's signature set piece is a montage of Louis-heeled Manolo Blahnik shoes in Easter-egg colors, filmed in fetishistic close-up to the strains of Bow Wow Wow singing "I Want Candy." It's exhilarating in the style of a high-end television commercial or magazine fashion spread. But, by linking the excesses of the French court of the 1780s with the pop culture of the 1980s, does Coppola intend to suggest that we're overdue for another revolution? Or just that, then as now, les filles just want to have fun? [...]

In a Vanity Fair profile last month, Evgenia Peretz wrote about the director's nontreatment of the rioting French proletariat in Marie Antoinette: "In neglecting them she has unwittingly taken a political stance." Unwittingly? It seems disingenuous to suggest that a movie about the fall of the French monarchy could be anything but political. I don't ask Coppola to be unsympathetic to the young queen, or even to devote any screen time to her arrest and decapitation. (The film ends abruptly as Jason Schwartzman's King Louis XVI and his queen flee Versailles in their royal coach after the storming of the Bastille.) But just because the film's heroine has nothing to say about politics, revolutionary or otherwise, doesn't justify Coppola being similarly dumbstruck.

"It's not like I'm a royalist," Coppola protested in a recent interview, when asked about her curiously blank take on the French Revolution. I'll take her word for it, but you'd never know it from the movie she's made, which is at least as nostalgic about the ancien régime as Gone With the Wind is about the antebellum South. Coppola's heroine lodges a similar protest in the film upon hearing about her alleged wish for the starving masses to nourish themselves on cake. "I would never say that!" the queen comments, shocked, to her ladies in waiting. According to the Antonia Fraser biography Marie Antoinette is based on, she never did say those actual words—but the rest of the film shows her as exactly the kind of person who would say them, so what's the difference? [...]" Source: Slate (by Dana Stevens)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And the most negative, the third review by Lawrence Toppman for "The Charlotte Observer":

"After seeing Sofia Coppola's "Marie Antoinette," I realize there was no need for the bloodshed and turmoil of the French Revolution that made Marie and husband Louis XVI shorter by a head. Had the mobs left them alone, they'd have bored themselves and everyone else in the aristocracy to death. [...]

Marie celebrates her 18th birthday in 1773 in the scene just before Louis decides to help America in the Revolutionary War. (Nice of him, as it didn't start for three more years.)

Even Coppola's infamous decision to set the movie to New Wave pop music seems ill-judged, because she's not consistent. We get a "Pretty Woman"-style clothes-and-footwear romp to Bow Wow Wow's "I Want Candy," and then we're back to baroque-style chamber ensembles droning away for 15 minutes.

The casting is also unhelpful. Kirsten Dunst alternates between giddy smiles and a faux-pensive look as Marie, though the prospect of imminent death troubles her as little as an absence of petit-fours. (Or "petite fours," as Schwartzman's Louis would say.) Schwartzman tamps down his California cockiness but looks perennially uneasy, as if wondering whether his wig might be tumbling off. Both are as pinkly prettified and devoid of emotion as fresh corpses.

Supporting characters have energy, but the wrong kind. Rip Torn leers genially and blankly as Louis XV. Italian-born Asia Argento sneers as his mistress, Madame du Barry, like a high school girl from North Jersey planning to poke out a rival's eyes with a rattail comb. Judy Davis, whose twitchiness suggests the affliction of St. Vitus' dance, manages to overact even in scenes where she doesn't speak.

Coppola has said in interviews that she doesn't want to explain the movie, which follows an apparently ageless Marie and Louis from their nuptials in 1770 to arrest by the mob in 1789. But what can she want us to take away?

Are we supposed to accept the fatuous idea that teenagers have behaved the same in all eras? (Hardly true. Royals took on adult responsibilities as teens back then and were trained and educated differently.) Should we have special sympathy for this vacuous creature who stood by her equally clueless husband en route to disaster? The movie's not particularly kind to either: She comes off as a gluttonous airhead, he an amiable plodder.

The ultimate irony of the project is that Marie and Louis' main crime was self-indulgence: They had too little awareness of the discrepancy between themselves and their people, and they paid for ignorance with their lives. But if self-indulgence justified regicide, Queen Sofia would be ready for Hollywood's guillotine."Source URL: https://americanendeavor.blogspot.com/2006/10/three-more-ma-reviews_28.html

Visit american endeavor for Daily Updated Hairstyles Collection

Just as Tobey Maguire proved that the superhero is about the vulnerability, Kirsten Dunst nicely unveils the innocence in the doomed queen of France.

The 1980s score and 818 dialogue ("I love your hair! What's going on there?") may strike you as a little too droll for l'école. But the story follows Antonia Fraser's biography, and the crazy flourishes simultaneously blast away the musty mists of history and make the audience feel, as the Austrian-born queen must have, lost in translation. [...]

Dunst, tearfully parting with her pug as her character exits Austria, practically has a dotted line around her neck with instructions to "cut here," and she makes no effort to starch up her squeaky American cuteness. But though the real Marie Antoinette was born an archduchess, she was no older than a highschool freshman when she married. After that, she was just a victim of fashion, a pleated skirt when history went Goth. Her story could just as easily be called "Clueless."

kyle.smith@nypost.com Source: The New York Post

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Sofia Coppola is the Veruca Salt of American filmmakers. She's the privileged little girl in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory whose father, a nut tycoon, makes sure his daughter wins a golden ticket to the Willie Wonka factory by buying up countless Wonka bars, which his workers methodically unwrap till they find the prize. If Coppola's 2004 Academy Award for best original screenplay for Lost in Translation was her golden ticket to big-budget filmmaking, Marie Antoinette is her prize, a $40 million tour through the lush and hallucinatory candy land of 18th-century France. Of course, Roald Dahl's insufferable Veruca Salt was eventually seized by angry squirrels and hurled down a garbage chute. [...]

Given the film's cavalier treatment of their country's history, French critics, understandably, head up the haters' brigade. Agnès Poirier, the London correspondent for Libération, scoffs, "There are two things [Coppola] likes, dresses and pudding. ... Cinema is for Coppola a mirror in which she looks at herself, not a mirror she holds to the world." But many critics on both sides of the Atlantic defend the film, in indulgent language that often seems to apply to its creator as well. To Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwarzbaum, Marie Antoinette is "the work of a mature filmmaker who has identified and developed a new cinematic vocabulary to describe a new breed of post-postpostfeminist woman." (The triple negative threw me for a minute, but I think she means "not feminist.")

There's no question that making movies is, at least in part, always a matter of shopping. A director must select, and find a way to pay for, the right cast, the right music, the right cinematographer. And, as this recent piece in the Times travel section shows, Sofia Coppola is a peerless shopper. The movie's signature set piece is a montage of Louis-heeled Manolo Blahnik shoes in Easter-egg colors, filmed in fetishistic close-up to the strains of Bow Wow Wow singing "I Want Candy." It's exhilarating in the style of a high-end television commercial or magazine fashion spread. But, by linking the excesses of the French court of the 1780s with the pop culture of the 1980s, does Coppola intend to suggest that we're overdue for another revolution? Or just that, then as now, les filles just want to have fun? [...]

In a Vanity Fair profile last month, Evgenia Peretz wrote about the director's nontreatment of the rioting French proletariat in Marie Antoinette: "In neglecting them she has unwittingly taken a political stance." Unwittingly? It seems disingenuous to suggest that a movie about the fall of the French monarchy could be anything but political. I don't ask Coppola to be unsympathetic to the young queen, or even to devote any screen time to her arrest and decapitation. (The film ends abruptly as Jason Schwartzman's King Louis XVI and his queen flee Versailles in their royal coach after the storming of the Bastille.) But just because the film's heroine has nothing to say about politics, revolutionary or otherwise, doesn't justify Coppola being similarly dumbstruck.

"It's not like I'm a royalist," Coppola protested in a recent interview, when asked about her curiously blank take on the French Revolution. I'll take her word for it, but you'd never know it from the movie she's made, which is at least as nostalgic about the ancien régime as Gone With the Wind is about the antebellum South. Coppola's heroine lodges a similar protest in the film upon hearing about her alleged wish for the starving masses to nourish themselves on cake. "I would never say that!" the queen comments, shocked, to her ladies in waiting. According to the Antonia Fraser biography Marie Antoinette is based on, she never did say those actual words—but the rest of the film shows her as exactly the kind of person who would say them, so what's the difference? [...]" Source: Slate (by Dana Stevens)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And the most negative, the third review by Lawrence Toppman for "The Charlotte Observer":

"After seeing Sofia Coppola's "Marie Antoinette," I realize there was no need for the bloodshed and turmoil of the French Revolution that made Marie and husband Louis XVI shorter by a head. Had the mobs left them alone, they'd have bored themselves and everyone else in the aristocracy to death. [...]

Marie celebrates her 18th birthday in 1773 in the scene just before Louis decides to help America in the Revolutionary War. (Nice of him, as it didn't start for three more years.)

Even Coppola's infamous decision to set the movie to New Wave pop music seems ill-judged, because she's not consistent. We get a "Pretty Woman"-style clothes-and-footwear romp to Bow Wow Wow's "I Want Candy," and then we're back to baroque-style chamber ensembles droning away for 15 minutes.

The casting is also unhelpful. Kirsten Dunst alternates between giddy smiles and a faux-pensive look as Marie, though the prospect of imminent death troubles her as little as an absence of petit-fours. (Or "petite fours," as Schwartzman's Louis would say.) Schwartzman tamps down his California cockiness but looks perennially uneasy, as if wondering whether his wig might be tumbling off. Both are as pinkly prettified and devoid of emotion as fresh corpses.

Supporting characters have energy, but the wrong kind. Rip Torn leers genially and blankly as Louis XV. Italian-born Asia Argento sneers as his mistress, Madame du Barry, like a high school girl from North Jersey planning to poke out a rival's eyes with a rattail comb. Judy Davis, whose twitchiness suggests the affliction of St. Vitus' dance, manages to overact even in scenes where she doesn't speak.

Coppola has said in interviews that she doesn't want to explain the movie, which follows an apparently ageless Marie and Louis from their nuptials in 1770 to arrest by the mob in 1789. But what can she want us to take away?

Are we supposed to accept the fatuous idea that teenagers have behaved the same in all eras? (Hardly true. Royals took on adult responsibilities as teens back then and were trained and educated differently.) Should we have special sympathy for this vacuous creature who stood by her equally clueless husband en route to disaster? The movie's not particularly kind to either: She comes off as a gluttonous airhead, he an amiable plodder.

The ultimate irony of the project is that Marie and Louis' main crime was self-indulgence: They had too little awareness of the discrepancy between themselves and their people, and they paid for ignorance with their lives. But if self-indulgence justified regicide, Queen Sofia would be ready for Hollywood's guillotine."Source URL: https://americanendeavor.blogspot.com/2006/10/three-more-ma-reviews_28.html

Visit american endeavor for Daily Updated Hairstyles Collection

No comments:

Post a Comment